ELECTRIC MELTING 22/02/2021

In responsible manufacturing of stone wool, electric melting is a hot topic. Thanks to electric melting, products such as Natura Lana, Paroc’s new carbon neutral insulation product, can be manufactured. This melting technology arrived at Owens Corning Paroc’s factory in Finland 35 years ago. It would take decades before any other company started using it. This advantage has created Paroc a wealth of knowledge.

This is something we are very proud of: Paroc was the first stone wool manufacturer in the world to begin using electric melting on an industrial scale. This took place already back in 1986 at the Parainen factory in Finland. Paroc built large-scale electric melting furnaces also in Poland in 2008. By that time similar furnaces had started to appear also in other companies.

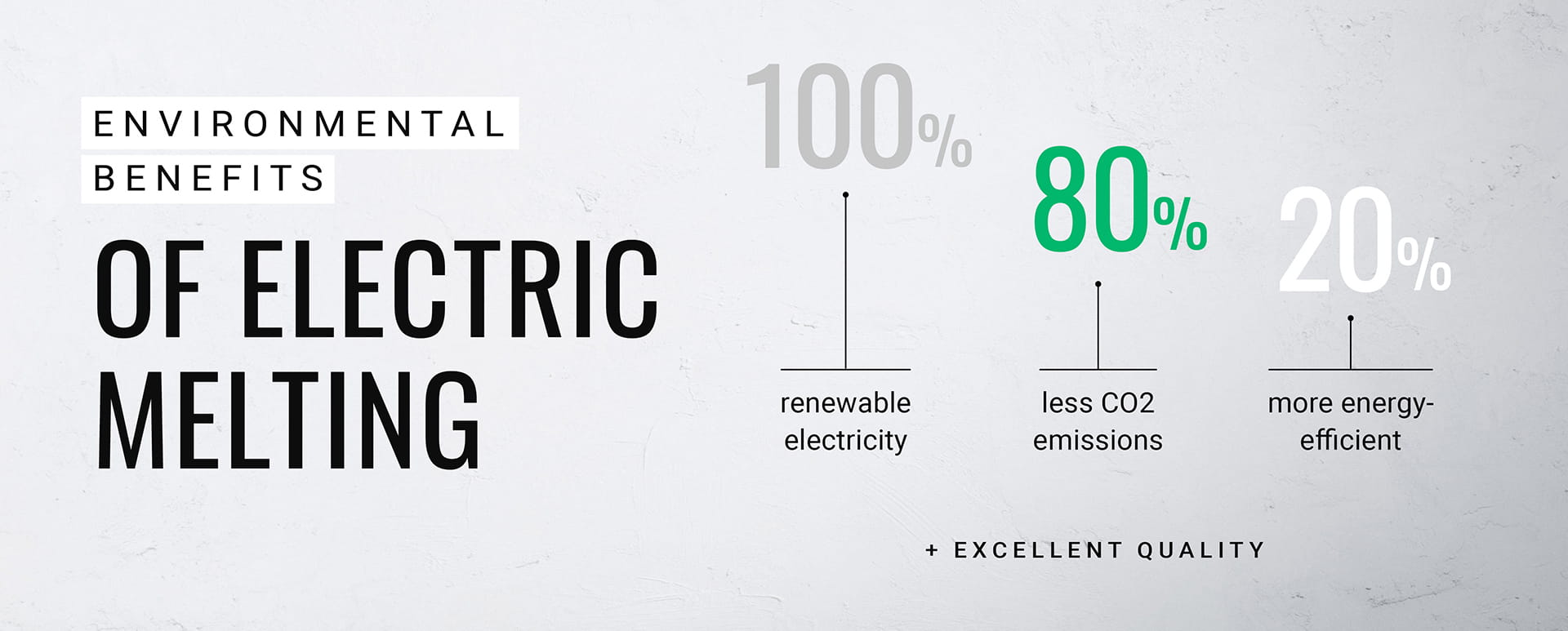

Nowadays, using an electric melting furnace in manufacturing stone wool is a hot topic because of its environmentally friendly qualities.

“An electric melting furnace is around 20% more energy efficient than using a coke-fired cupola furnace. With electric melting technology, we can use green electricity which creates 80% less CO2 emissions compared to using a cupola furnace”, says Niklas Bergman, R&D Program Leader at Owens Corning Paroc.

Electric melting has also enabled the creation of PAROC® Natura Lana. The carbon neutral stone wool insulation is available from February 2021 onwards. Read here to find out more.

“We have noticed that the best product quality also comes from our electric melting production line”, Bergman says.

The technology sounds sensible in every aspect. Nevertheless, Paroc’s pioneering work in the development of electric melting has been anything but easy.

Paroc actually originally acquired the only industrial-scale electric furnace in the world for the product quality it produces.

Paroc’s factory in Lappeenranta, Finland, had had a small melting furnace that used electricity already in the 1950s. It produced a better-quality fiber than the products manufactured with a cupola furnace. One of the most important topics in the 1980s was the sulphur emissions deriving from coke. At the time, CO2 emissions were not taken into consideration. The price of coke was also on the rise.

This is why Paroc was looking to create something new. At the time, a bigger investment was made in the development of stone wool, and melting was a part of it. Development engineer Carl-Gustav Nygårdas was appointed Head of the electric melting project.

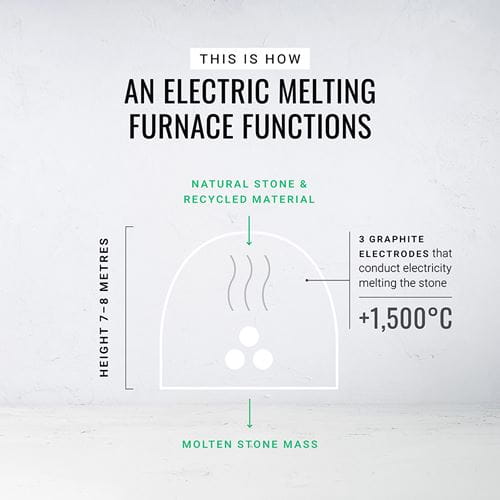

First, the team traveled the world looking for a manufacturer to build a melting furnace suitable for manufacturing stone wool: it should be around 8 meters high with a furnace body with a capacity of 50 tonnes as well as three large graphite electrodes to conduct electrical currents needed to melt the stone into a 1,500°C molten mass.

A manufacturing partner was found in Asia. The Paroc team told their new partner the details and lessons they had learned while operating the tiny melting furnace in Lappeenranta.

But with an industrial-sized furnace came also some industrial-sized challenges. For example, on New Year’s Eve 1987, the carbon coating of the electric melting furnace corroded. This required quick measures as there were 50 tonnes of molten stone that needed to be drained.

In moments like that, there was nobody in the world to turn to. No one to call for advice. You simply had to sit down at the factory, think and come up with a solution together.

Carl-Gustav Nygårdas frankly admits that the first years of the project were difficult.

“I was losing my sleep and my temper frequently”, Nygårdas reminisces but is nowadays able to laugh at all the setbacks. Nowadays, he refers to them as adventures.

Nonetheless, the objectives were achieved: the molten material was of a quality that they expected and later the significant environmental benefits also became evident. However, the most important accomplishment was the wealth of knowledge and lessons amassed from having pioneered such an endeavour.

“It takes decades to learn all the intricacies of electric melting. In 2010, when I retired, there were still matters that needed to be figured out, and we have come a long way even during the past decade.”

So, whose idea was the electric melting furnace originally?

Carl-Gustav Nygårdas thinks back remembering it was Niklas Bergman’s father, Gunnar Bergman, who was the development manager at the time. He was the one often talking about it.

Paroc’s factory in Parainen, Finland, has traditionally been a place that has nurtured long careers and people passionate about their work. Gunnar Bergman was hired to work in the development department when Niklas was 2 years old. Niklas got to visit the factory as a child and later they talked about work so much that he could have been manufacturing stone wool already at the age of 15. Now Niklas, 50, has built his entire career working at Paroc’s R&D department.

“The skills of the factory staff are immensely important. It takes years of experience to learn how to operate an electric melting furnace efficiently”, Niklas Bergman says.

The weighing and dosing accuracy of the raw material – natural stone and recyclable waste suitable for re-use – is a meticulous task. The chemical composition of stone wool fiber requires following strict criteria.

Niklas Bergman points out that there is always someone monitoring the round-the-clock production. It is more arduous and expensive than using a traditional cupola furnace which is the reason why its use has increased around the world only in the recent years.

Then again, this is how new innovations emerge. PAROC® Natura Lana is an excellent example of the results of pioneering work.